Ivory plaque with Phoenician inscription

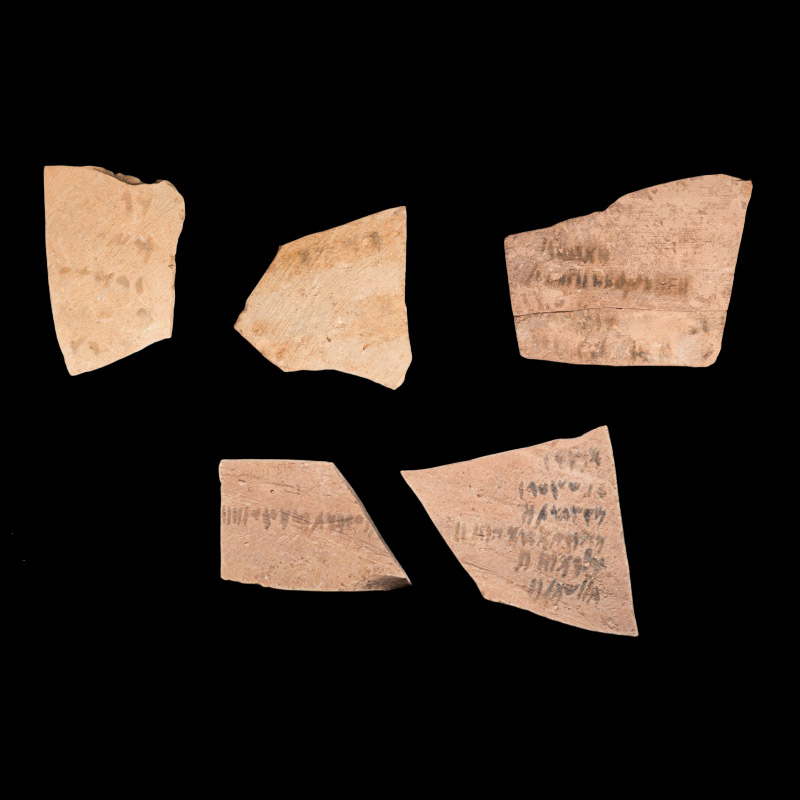

Fragments of painted epigraphic amphorae

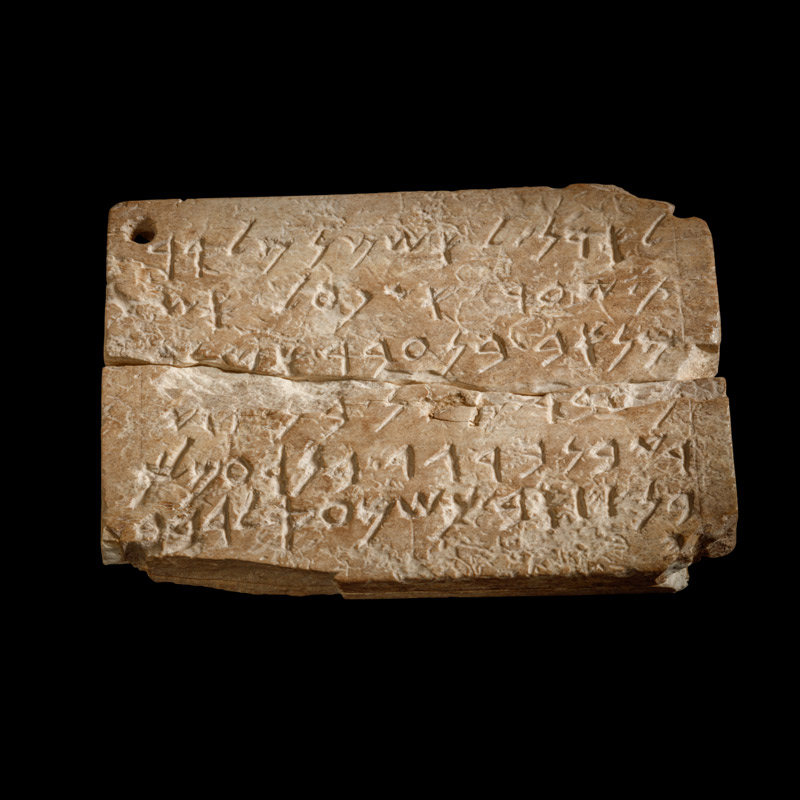

Sculpture base dedicated to Melqart or Melkart

Marble with an incised Phoenician inscription. 3rd century BC. Recovered during the excavations of Joan Planells, directed by Glenda Grazziani. MAEF.

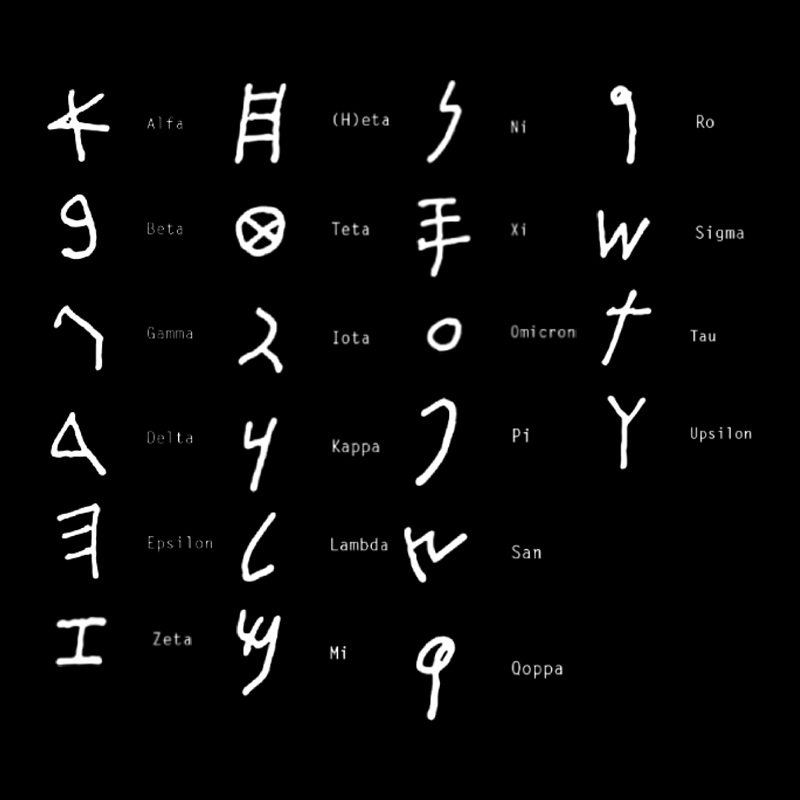

Phoenician writing, the basis of numerous alphabets, was used by the Phoenicians and other Canaanite cultures. With 22 consonant letters, it influenced later languages. Although it originally lacked vowels, it evolved with the use of mater lectionis to represent them.

BEYOND THE ALPHABET

The Phoenician skill in trade and navigation contributed to the spread of their linguistic and written legacy throughout the Mediterranean, and their inherited and modified alphabet served as a starting point for the development of various scripts, including Greek, Latin and, finally, many of the modern alphabetic systems we use today.

The Phoenicians did not invent the alphabet from scratch; rather, they inherited a more complex writing system and transformed it into a more efficient alphabet. They significantly reduced the number of characters, simplifying it to an alphabet of only 22 consonant letters.

The advancement of writing was essential for developing societies, being crucial in commerce, diplomacy, legislation, justice, religious expressions and, fundamentally, to transmit their history. This progress coincided with the Phoenician and Greek colonizing lines.

WRITING MATERIALS

The Phoenician texts found have been scarce, largely due to the perishable nature of the materials used; Papyrus, skins and plant materials were the usual writing materials for Phoenician writing. The texts written on these materials could be incised, stamped or painted.

PHOENICIAN WRITING IN IBIZA

In Ibiza there is one of the most important sets of examples of Phoenician writing in the entire western Mediterranean. Particularly noteworthy is the plaque belonging to es Culleram cave-sanctuary from the 4th century, written in Neo-Punic.

Recently discovered, two inscriptions stand out. One, dated around the 6th century, was found on ivory, while the other, from the 5th to the 4th century, was found on marble. These were discovered at the Joan Planells archaeological site.

These epigraphic samples, of a votive nature, are closely linked to religious cults, expressing requests and prayers. Furthermore, as a testimony of trade during this period, various ceramic inscriptions have been found at the Castell de Dalt Vila site.

I’dn l’ršp mlqrt mqd (š)

z ´s ndr ´s´ dr bn ´s(y)

bn brgd bn šmnhl(Ş)

“Per el senyor Reixef Melgart aquest san-tuari que ha dedicat Eixaddir fill de Aixi

fillde Bergad fill de Eixmunkhil-lets”

Inscription on a bronze plaque from the Culleram Sanctuary. 4th century BC.

p`l wndr whdš yt hgzl

st `bd´smn bn `zrb`l

hkhn lrbtn ltnt ‘drt

whgd wb`l hrš h’ btm

“ha fet i ha dedicat i ha renovat el mur

aquest Abdeixmun fill d’ Azarbaal

el sacerdot per la nostre senyora per Tanit poderosa

i la afortunada i l’arquitecte aquell (ell) va construir”

Inscription on a bronze plaque from the Culleram sanctuary. 4th century BC.

I´dn l´šmn w Irb

t l`sr(t?) ´z p`l ´s

mn’b bn `bd(ms…)

n`bd…n bn (g)y

ry bn bdgd bn d`mlk

bn ´hb kšm`ql dbr

y

“Per el senyor, per Eixmun iper BI senyo-

ra per Aixtart això que ha fet

Minab () fill de Abd..

fill de Abd…n fill de (G)ui-

rai(?) fill de Bodgad fill de Daamilk

fill de Akhab perquè ha escoltat la veu de la seva pa-

raula”

Inscription on the bone plaque found during the excavations on Joan Planells Street. 6th century BC.

l´dn lmlqrt `l hsr s(ml)

hrs dl hktrt šlm (ndr)

b`m tg ´lbn kš(m`) (ql´)

“Per el senyor per Melqart sobre Tir (estàtua)

d’or amb pedestal ha complert (el vot)

del poble de Tglbn perquè ha es(coltat la seva veu)”

Inscription on the marble plaque found during the excavations on Joan Planells Street. 3rd-2nd century BC.

From Sa Caleta on Phoenician Writing

From

Sa Caleta on

Phoenician

Writing

RELIGION

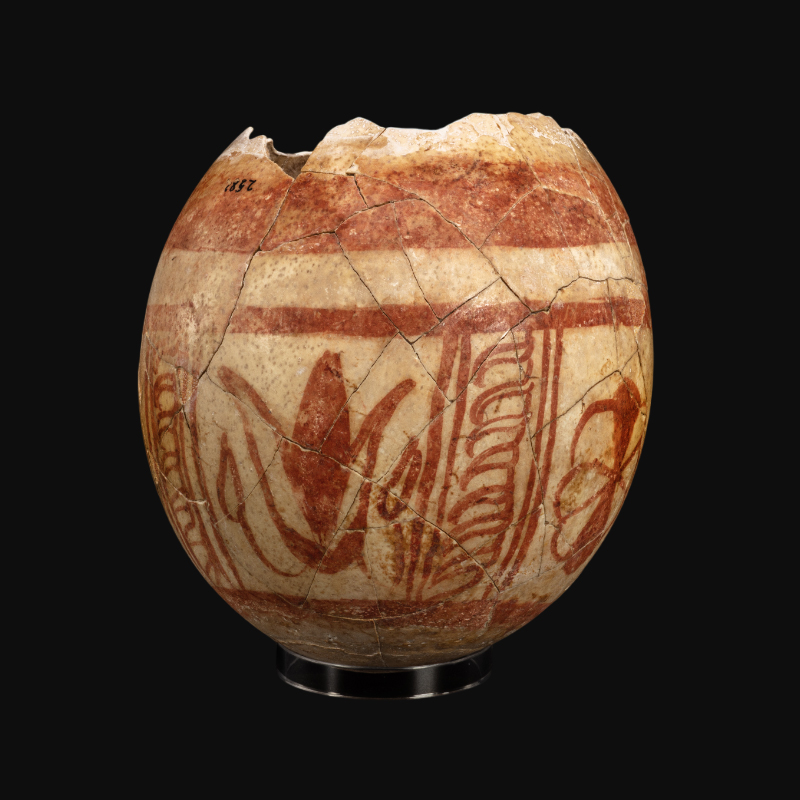

Decorated ostrich egg shells

Glass pendant

Ceramic molds

Representation of the god Bes (300-200 BC). The god Bes probably gave his name to Ibiza (‘Ybshm = islands of the god Bes). MAEF.

Polychrome glass paste pendant

The Phoenician culture had an extensive pantheon comprised of a variety of gods to worship. These deities were present in different aspects of life, such as trade, travel, family and in the transition to the afterlife.

PHOENICIAN DIVINITIES

The pantheon of Phoenician gods included notable figures such as Melkart, Tanit, Astarte and Bes. Melkart, originally a deified king of Tyre, was revered as the protector of trade and colonization, with temples erected in the colonies. Astarte, his wife and goddess of Sidon, represented fertility, love and war. In Carthage, Tanit was an important deity, associated with Baal Hamon and with attributes similar to those of Astarte. This diversity of deities reflects the complexity and richness of Phoenician religion.

THE PLACE OF WORSHIP

Devotion towards the divine was manifested in the construction of temples, such as that of Melkart in Cádiz. These temples not only served as places of worship, but also as administrative and financial centres where prices and weights were established. In addition, temples were spaces where precious products and wealth were stored and guarded.

In Sa Caleta, a house has been documented in the South neighbourhood area with unique characteristics, accompanied by a set of materials that suggest a possible sacred character, which could indicate the presence of a temple or cult space. This room consists of an anteroom, a prayer and ritual room, and a third space probably used for storage.

Also notable is a one-room house with a central hearth and partially paved with pebbles. Burned human remains were found in this room, the use and importance of which is still not fully understood in the Sa Caleta settlement.

THE OFFERINGS

The Phoenicians believed in omnipotent and omnipresent gods who influence people’s lives. They practised continuous prayers and sacrifices, such as animal offerings, especially ovicaprids and bovines. Furthermore, to appease specific gods such as Moloch or Astarte, they carried out the cremation of deceased children or practised hierogamy in temples or sacred prostitution.

JOURNEY TO THE UNDERWORLD

In Sa Caleta no human remains have been found that suggest the existence of a “City of the Dead”, it is plausible that coastal erosion has affected this sacred space. After the abandonment of the site and the founding of Ibosim, a large necropolis emerged in the area today known as Puig des Molins.

From

Sa Caleta

on religion

From Sa Caleta on religion